Simultaneous localisation and mapping (SLAM) has been subject of research for roboticists for decades. Learning a robot to navigate in an uncontrolled, unknown environment is far from trivial. On the one hand, the robot must know where it is on a map, i.e. the “localisation”, on the other hand, the robot should build the map for places it hasn’t visited before, i.e. the “mapping”. Typical SLAM approaches used in robotics build an euclidean 2D (or 3D map) of the environment, where they assign certain features to x,y(,z) coordinates. This feature could simply be a 0 or 1 indentifying whether this coordinate is “occupied” by something, e.g. when a laser beam is reflected from that point, or a visual feature descriptor of the image patch from that location in the case of a camera sensor. When the robot then observes enough of these features relative to its own location, this may be sufficient to get an estimate of its location on the map.

This approach works very well in the case of perfect sensing and fixed environments. However, the real world is nothing like that. In the real world, the environment constantly changes. Each and every day, your chair is at a slightly different location, you leave stuff at different places, doors can open and close, etc. These changes render the map incorrect and make it troublesome to correctly localise. Also the appearance of features of the map can change over time, for example the day-night cycle has a big impact on the lighting conditions for camera-based SLAM. Finally, also our sensing devices are not perfect. Slight errors may accumulate over time, or sensors might fail completely such as cameras and lidars in direct sunlight.

So how do humans do it?

Humans on the other hand, as well as a plethora of other living creatures on this wonderful planet, have little difficulties navigating these harsh, real-world environments. We navigate our house, our office, our town every day, with far less accurate sensing devices (for example, we don’t have mm accuracy range sensing). Unlike these robots, we don’t have a detailed, metric map in our head. In effect, orienting and navigating using a 2D metric map is difficult for a lot of people, and is a skill acquired through training. We do however recall certain landmarks that are useful for localising (e.g. “I’m next to a church”), or that have salient information for navigating (e.g. “take the second door on the right”).

Similarly, research on rodent brains of rats navigating mazes have shown the existence of cells that encode exactly this kind of salient information. Place cells fire when a rat visits a particular place in a maze, and border cells fire when a border in a certain direction is faced 1. On the other hand, also grid cells and head direction cells were discovered that encode a rough pose estimate of the rats head 2. So it seems that our brains are somehow roughly tracking our pose in the world, localizing itself by recognizing particular places.

A generative world model for navigation

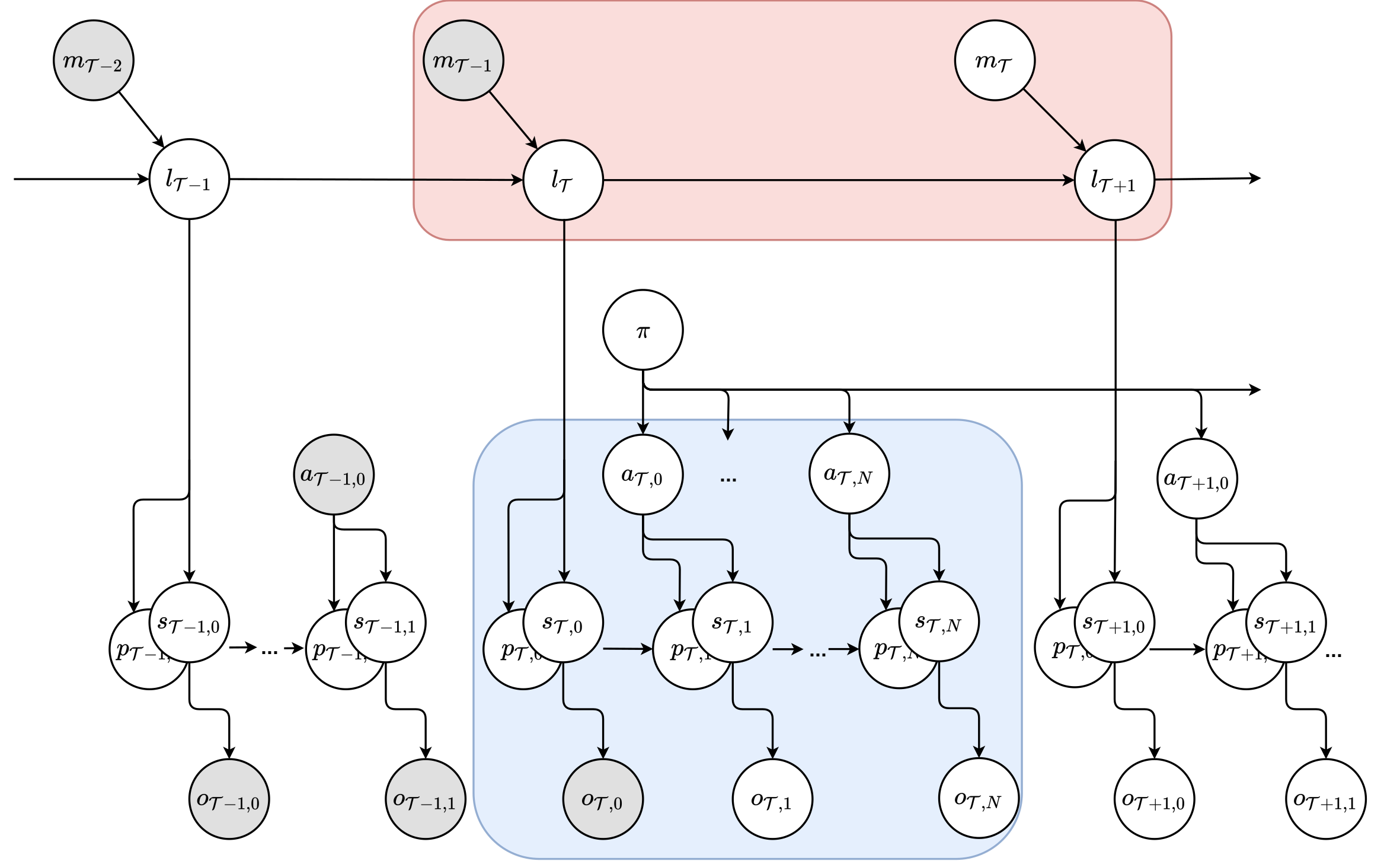

Based on this we can define a generative model for an agent navigating its environment. Similar to a Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (POMDP), each timestep \(t\) the agent can perform actions \(\textbf{a}\) and has access to sensory observations \(\textbf{o}\). These observations are assumed to be caused by some hidden state \(\textbf{s}\), which the agent has to infer.

We extend this model in two ways. First, we assume part of the state must somehow encode the agent’s pose \(\textbf{p}\) in the world, similar to the grid and head direction cells mentioned earlier. Second, we add a level of hierarchy in which the agent can reason on a more coarse-grained level about the world, as moving from location to location. At this level, the agent forms believes over it’s current location \(\textbf{l}\), and can perform a move \(\textbf{m}\) to another location. The location of the agent will determine the low level state \(\textbf{s}\), and vice versa the low level state will provide evidence for the agent to infer its current location.

Hierarchical active inference

If you have read our previous blog posts, you might be familiar with active inference. In a nutshell, active inference states that intelligent behavior emerges from agents building a generative model of their environment, and constantly trying to minimize a variational bound on “surprise”, the so-called free energy. Having just introduced a special kind of hierarchical generative model suited for navigation, what happens if we provide it to a free energy minimizing agent? Well, in our paper we show that such an agent will build a cognitive map of its environment, and be able to navigate this map. Not only do we derive the math, but we also built a working example of such an agent. In effect, our LatentSLAM framework can be seen as an implementation of this kind of generative model. In addition, by also inferring actions that will minimize expected free energy in the future, the agent will engage in path planning on the highest hierarchical level, seeking the shortest and least ambiguous path to goals, and develop low-level control policies that trade-off staying on the route versus avoiding surprises, e.g. similar to obstacle avoiding behavior.

What’s next?

We have shown that simultaneous localization and mapping emerges naturally from a free energy minimizing agent equipped with a hierachical generative world model. Our current implementation illustrates that this indeed results in sensible cognitive maps, and that meaningful policies arise when minimizing expected free energy. However, the resulting policies are only as good as the model, and hence the data collection phase is crucial for the success of the robot. Currently, we also pretrain the model offline on a collected dataset. We are now looking into online and continual learning schemes, that allow the robot to explore and gather the data necessary to improve its model. Also this exploratory, information seeking behavior emerges from active inference, but is not straightforward to implement on a real robot.

Also, as mentioned before, we currently have enforced a part of the state space to encode an estimate of the agent’s pose \(\textbf{p}\) in the world. An intruiging research question is whether this indeed has to be imposed, whether the agent will naturally learn pose encodings in its state space purely from data, or whether some inductive bias is required for the model to give rise to grid and place cells. This might shed a new light on how humans and other animals are able to navigate, and foster novel theories on the inner workings of our brain.