Active Inference is a brain-inspired theory according to which all living beings (aka agents) behave according to a unicum imperative: minimizing their free energy. This means that the brain learns a model of the world, to predict future events, and uses this model to decide what actions to take. For a deeper introduction to Active Inference, you can have a look at our previous post.

What does minimizing free energy imply in terms of behavior? That any agent would use its model to plan future actions in a way that will lead to satisfying its preferences, in the least ambiguous way possible.

In this post, we introduce our Contrastive Active Inference implementation that allows fulfilling preferences with Active Inference, in visual and complex environments. For full details, please check out our paper, published at the NeurIPS 2021 conference.

Satisfying Preferences

What are preferences in Active Inference? We can define them as sensorial perceptions that an agent would like to obtain, in order to feel satisfied, or accomplished, or pleased.

For instance, the human body has a preference for temperatures around 37° Celsius (~ 99° Fahrenheit). If it’s too cold or too hot, a person generally looks for ways to warm up or cool down. These preferences are naturally available in the real world, as they are part of the phenotype of an agent.

In Machine Learning, and in particular, in Reinforcement Learning, preferences are represented with a reward function that provides a positive signal for behaviors that are correct and we want to reinforce. However, there’s a flaw in this process: the reward function needs to be engineered for all possible states and actions of the world, as they are not naturally available.

How easier would it be if we could just provide an image that represents the goal we want to achieve?

Significantly easier! However, satisfying preferences in high-dimensional spaces, such as in pixel space for visual environments, can be quite difficult.

For instance, imagine we want a robotic arm to reach a red sphere goal:

The image of the arm achieving the task could represent the preference of the robotic arm. We can also call this our goal image.

Now, let’s compare the distance between the goal image and two potential images from the environment. The first case is the goal image with some added random noise (left). The second image is an image of the robot arm in a wrong pose, that doesn’t accomplish the task (right).

The mean squared error (MSE) distance between the image with noise and the goal one is 21.74. The MSE distance between the wrong pose image and the goal one is 15.22.

This implies that, when working in pixel space, each time there is some unexpected noise or some visual variations, a problem occurs. The robotic arm can think that he’s not satisfying its preferences, while it actually is, or it might even believe that a wrong pose is better than the correct one.

How can we overcome such a problem?

Contrastive Learning to the rescue!

Contrastive Learning is a method to learn representations based upon similarity. The contrastive mechanism enforces that in the representational space similar pairs of concepts are close, while dissimilar pairs of concepts are far.

The choice of what is similar and dissimilar depends of course on the task. We could for instance desire a representation where objects with the same colors are similar, and objects with different colors are dissimilar.

In this example, contrastive learning will push the representations of objects with the same color closer in the representation space and the representations of objects with different colors farther.

From an information-theoretic point of view, learning with a contrastive objective minimizes an upper bound on mutual information, between the concepts we would like to encode and their representations. For further details on this and on contrastive learning representations, we suggest looking into this reference.

Contrastive Active Inference

Our method, which we dubbed Contrastive Active Inference, is an Active Inference instantiation based upon Contrastive Learning. The objective of the agent is always to minimize its free energy. Though, the way it learns to do it it’s based on Contrastive Learning. Let’s see how!

In Active Inference, the brain first learns a model of the environment. This model should capture how the environment’s state varies, due to the agent’s actions. If we perceive the environment through high-dimensional signals, such as images, we may desire a more compact representation to model the environment’s dynamics. This can generally be achieved by using a sequential VAE-like architecture, that learns to generate images that look like the environment’s visual observations pixel-by-pixel.

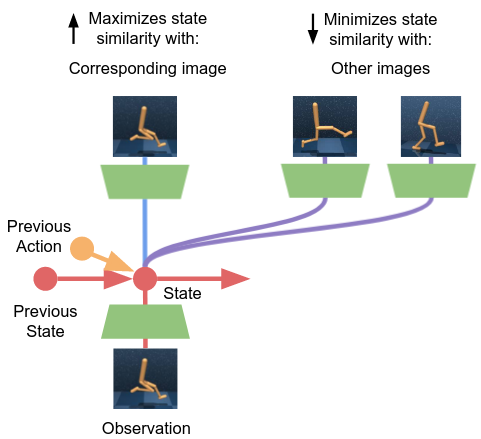

In our method, the compact representation for the world model is, instead, learned by minimizing a contrastive version of the free energy objective, which we called contrastive free energy. By minimizing this objective, the model learns to associate the state of the environment’s representation with the corresponding visual observation, while also making the state representation as distinct as possible from the other images. Similar and dissimilar pairs are selected contrasting observations across time and across different behavioral sequences.

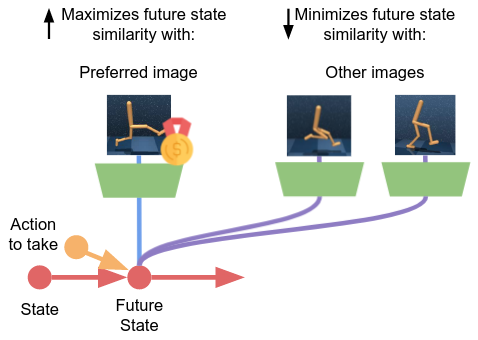

With respect to future actions, in Active Inference, we aim to find actions that will minimize free energy, by achieving preferences in an unambiguous way. If we use a VAE-like model for this, it implies imagining how the future will look like, by generating potential images of the future with the model, and computing the distance in pixel space. However, we have seen that this can be quite problematic.

In the Contrastive Active Inference framework, the agent selects actions that minimize a contrastive objective that we dubbed contrastive free energy of the future. This objective enables causes the agent to search for actions that will lead it to states that have the highest similarity with preferences, while avoiding states that correspond to different images.

This allows matching preferences within the state representation, avoiding the problem of generating images and measuring distances in pixel space.

Visual Control

We tested our method for visual control in different environments, interested in analyzing how the learning signal provided by Contrastive Active Inference differs and compares with respect to standard Active Inference (using a VAE-like model) and rewards (Reinforcement Learning)

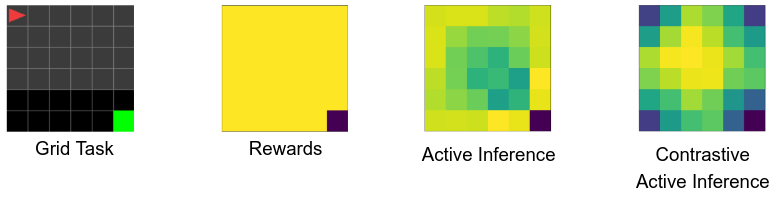

In a 2D Minigrid world visual task, we trained an agent (red arrow) to reach a goal (green tile) in a black grid. To comprehend how each method encourages reaching the goal, it is useful to analyze what’s the learning signal provided for each tile of the grid for each of the approaches.

We see here that Active Inference methods provide a denser signal than Rewards. “Standard” Active Inference provides a signal that it’s denser in the center, with the highest value in the goal tile. Contrastive Active Inference assigns higher values to all corners, with the highest value to corner with the goal tile.

This suggests that the contrastive mechanism assigns higher values to concepts that are closer to the goal (i.e. corners) rather than relying on pixel-wise differences in the images.

We also found Contrastive Active Inference allows successfully controlling a robotic arm on a plane to reach a goal (red sphere), learning from a single goal image (see above).

Complex Backgrounds

Following up on the robotic arm reacher experiment, we tested the different methods on a more complex task: controlling the robot to reach the goal, but with varying backgrounds and variations in the environment.

This version of the task is much more complex, as it’s difficult to learn a model that generates accurate images of the environment, due to the high level of detail in the background and to the visual variations between different sequences of actions. Here’s where contrastive learning comes to the rescue again!

We indeed found that both reward-driven methods and active-inference methods fail when using a VAE-like model. However, they manage to succeed in the task when using a contrastive learning model.

In particular, the Contrastive Active Inference method is able to achieve the task being provided the same goal image used for the simpler task, with no varying background (i.e. the original one with the blue-tiled background). This means that the contrastive mechanism allows to ignore differences in the background, favoring the imitation of the pose despite all the visual variations and complexities of the environment.

Future Perspectives

The Contrastive Active Inference work aims to provide a novel way of learning to achieve desired tasks, starting from visual preferences. Rewards, which have been fundamental until now to solve visual tasks, may be replaced in the future by more unsupervised objectives like ours.

We explored the mechanism of contrastive learning to relieve the model from generating accurate predictions in image space, and for facilitating the search of actions that would fulfill the preferences of the agent.

Our method provides a denser signal to learn, which overcomes several difficulties that occur when working in visual environments. Nonetheless, denser objectives are generally more difficult to optimize than sparser ones, and the risk to incur into local minima should not be neglected.

The results achieved with varying and complex backgrounds are promising for deploying Active Inference in more complex scenarios, such as real-world robotics, and should encourage more work in this direction in the future.